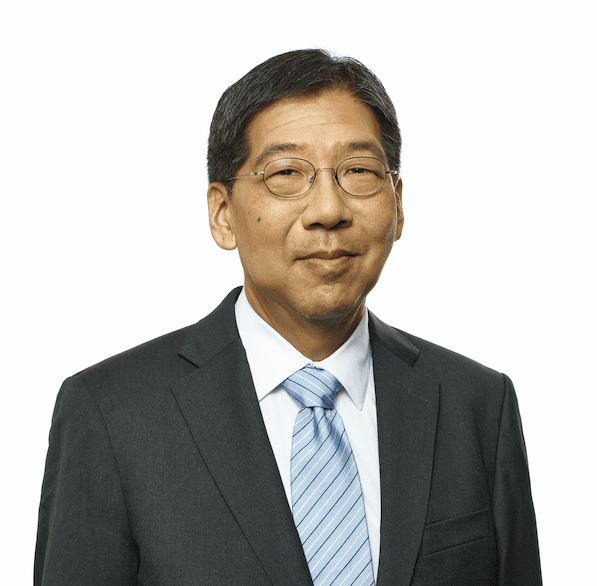

Face to face with Peter Chen

24th April 2019 –  Prof. Chen was born in 1960 in Salt Lake City, USA. He studied at the University of Chicago where he earned his degree in 1982 and was afterward awarded a doctoral degree in 1987 by Yale University. Following this, he began his independent career at Harvard University where he worked from 1988 to 1994, first as Assistant Professor, and then as Associate Professor. In 1994 he was elected Full Professor at ETH Zurich. In his research he combines detailed physical measurements with the planning and synthesis of molecules, making it possible to design and test intuitive models of the energetics and reactivity of reactive intermediates in organic and organometallic chemistry. Under normal conditions of reaction, these intermediate products have a very short life span, their behavior provides the key to the understanding and the control of the chemical process.

Prof. Chen was born in 1960 in Salt Lake City, USA. He studied at the University of Chicago where he earned his degree in 1982 and was afterward awarded a doctoral degree in 1987 by Yale University. Following this, he began his independent career at Harvard University where he worked from 1988 to 1994, first as Assistant Professor, and then as Associate Professor. In 1994 he was elected Full Professor at ETH Zurich. In his research he combines detailed physical measurements with the planning and synthesis of molecules, making it possible to design and test intuitive models of the energetics and reactivity of reactive intermediates in organic and organometallic chemistry. Under normal conditions of reaction, these intermediate products have a very short life span, their behavior provides the key to the understanding and the control of the chemical process.

Why did you become a scientist?

I’ve always wanted to be a scientist of one sort or another. My fundamental reason to become a chemist was that chemists make things. The French chemist, Marcellin Berthelot said ‘la chimie crée son objet’ (chemistry creates its object) —and it’s true: looking at science a bit tongue-in-cheek, physicists didn’t invent the universe, biologists didn’t invent life, but chemists’ study what they created. And that’s why I became a chemist, I like to make things.

What are the greatest achievements in your career so far?

Of the prizes that I have received, the one I’m most proud of is the “Golden Owl.” Every year, the students at the ETH vote for the best teacher in the department, and I’ve won twice: in 2005 and 2015! Only a few people got it twice, and this is for courses I taught in German, which is not my native language – so I am very pleased with that.

Do you think academics need to have an entrepreneurial spirit? Or ties with industry?

I think it’s important for academics to see themselves as in a privileged position where they can – and should – take risks. For chemists in academic research, it’s very important the contact with industry for two reasons. One, it keeps us realistic: it keeps us from going off into some esoteric area where it becomes more a philosophical argument than a scientific argument. The second thing is that industry is looking at chemistry with a 5-year timeframe, and in the academic world we should be looking at what will be important in 5 to 10 years. Academia should be ahead of industry, thinking about the things that industry is not thinking yet. But to do that you have to know what industry does: industry does a tremendous amount of research, some of which is never published, and there’s a lot of very good research there, with a lot of weird things that industry looks at but doesn’t pursue, and that could lead to an interesting question!

In your opinion, what areas of science are more important?

In general, the issue with complex systems, which includes all the fashionable stuff like big data, digitalization, etc. Typically, when we look at biological systems, they are immensely complex and self-regulated: secondary metabolism in living organisms, for example, is a vast net of highly regulated chemical reactions. If you think about disease, chemistry’s largest contribution to pharma and medicine has been “how do you kill something?” Find a chemical pathway which is unique to bacteria and inhibit it. This is a very crude approach to the system: just blow it up and hope you won’t kill the host. When you go beyond this, the next big challenges in medicine all have to do with problems in regulation: heart disease, diabetes– to some extent –, cancer, all the metabolic diseases that hit people as we age. All these are regulatory problems of complex systems, and this is far more difficult to address than simply blowing something up. If I was 30 years younger, this is something I’d find very attractive! I would try to intervene in regulatory pathways, or maybe build altogether synthetic ones.

What advice do you have for young researchers who want to become academics?

Always take the bigger risk, if you’re not going to take risks, don’t do research at all. If your work is too conservative, you’ll only have small results and at the end, that means you’ve got nothing. But, if you take a shot at the biggest thing you could think of, and it works, people will see you and you’ll make the next job. Don’t give up too easily when it’s hard, and don’t be satisfied too soon when it works, don’t be satisfied with small success. In academic careers, small success is no success, so you need to take the bigger risk because you have nothing to lose!

What would you do to address the gender gap?

I’ll give a microscopic example and a macroscopic example of what I’ve done. Of course, having a bit of executive decision power helps. But I think, these are two approaches that can bring more women into leadership positions in a short period of time.

In the microscopic scale, I was chair of a fellowship programme for postdocs at ETH that was funded by a generous donation from an ETH alumnus. From about 600 candidates, we invited ten for interviews and they all accepted, except one young woman who had just had a baby. So, we told her to bring the baby and got someone from the neonatal center from the university hospital to take care of it for the time of the interview and visit. Well, she ended up getting the fellowship and is now a professor. But she initially turned down the interview just because she didn’t have someone to take care of the baby, and that would have sidetracked her career for years. This is a problem that could be solved by money, and, frankly, in the overall scheme of things, not even a large amount of money. It required only the decision to do it, which was administratively possible because we were spending private money.

On a bigger scale, there’s a programme at the Swiss Science Foundation that identifies young women with high potential and funds them to have a fast start. If women are going to compete with men at the highest levels, they need to have what men always had: someone subordinated to take care of things for them. When men pursue a career, they don’t worry about household work, traditionally there was had someone else to take care of it. So, we put this big money prize and load it with prestige so that it’s socially acceptable for a woman to say “I’ve put my career first.” An important factor is that the money allows them to buy “non-traditional stuff” – childcare, house help, etc. It does not help a woman’s career to relieve her from committee, research, or teaching work, because this is what they need to compete in that career. But it does make sense to take away tasks that someone else can take care of. The social and economic problem is people outside say “Why does the academic woman get someone to do their groceries?” Well, the answer is that we are not talking about social justice here, but rather gender justice. If you want women to compete at a high level, you need to take away these things that other people can do. And this is a political argument that has to be made and which I think works.

If I went to Zurich what should I visit?

The milk chocolate factories, milk chocolate was invented in Zurich.

A chemical element: no particular element, I like them all!

A scientist: Pasteur, if you look at the idea of chirality, he had an observation of optical activity before there was any structural theory for molecules and he did this huge leap of intuition that the molecule itself was asymmetrical.

An invention: the Haber-Bosch process: it feeds over half the people in the world.

If you had not been a scientist: I’d be a lawyer, that was my plan B!

A destination: best holiday I’ve ever had was on Lanzarote. I liked Cesar Manrique’s large art projects, and it’s impressive that he convinced the government to fund public art on such a large scale. It’s aesthetically, artistically and environmentally consistent development.

A book: as a student, I read the Peloponnesian wars, Greek history. What’s frightening is that the book was written somewhat before 400C BC and it’s very 20th century: the political arguments, the description of motivations and the passions of man show that humans have changed very little, the scale has changed but the actual motivations and passions have not.

A movie: The Unforgiven by Clint Eastwood. It’s an unconventional Western that deals with the basic question of redemption and sin: is there good in an evil act?

A dream: never have to write a research grant again

Science is… a rational, humanistic way of looking at the world

Related news

Let's create a brighter future

Join our team to work with renowned researchers, tackle groundbreaking

projects and contribute to meaningful scientific advancements

27-03-2025

27-03-2025