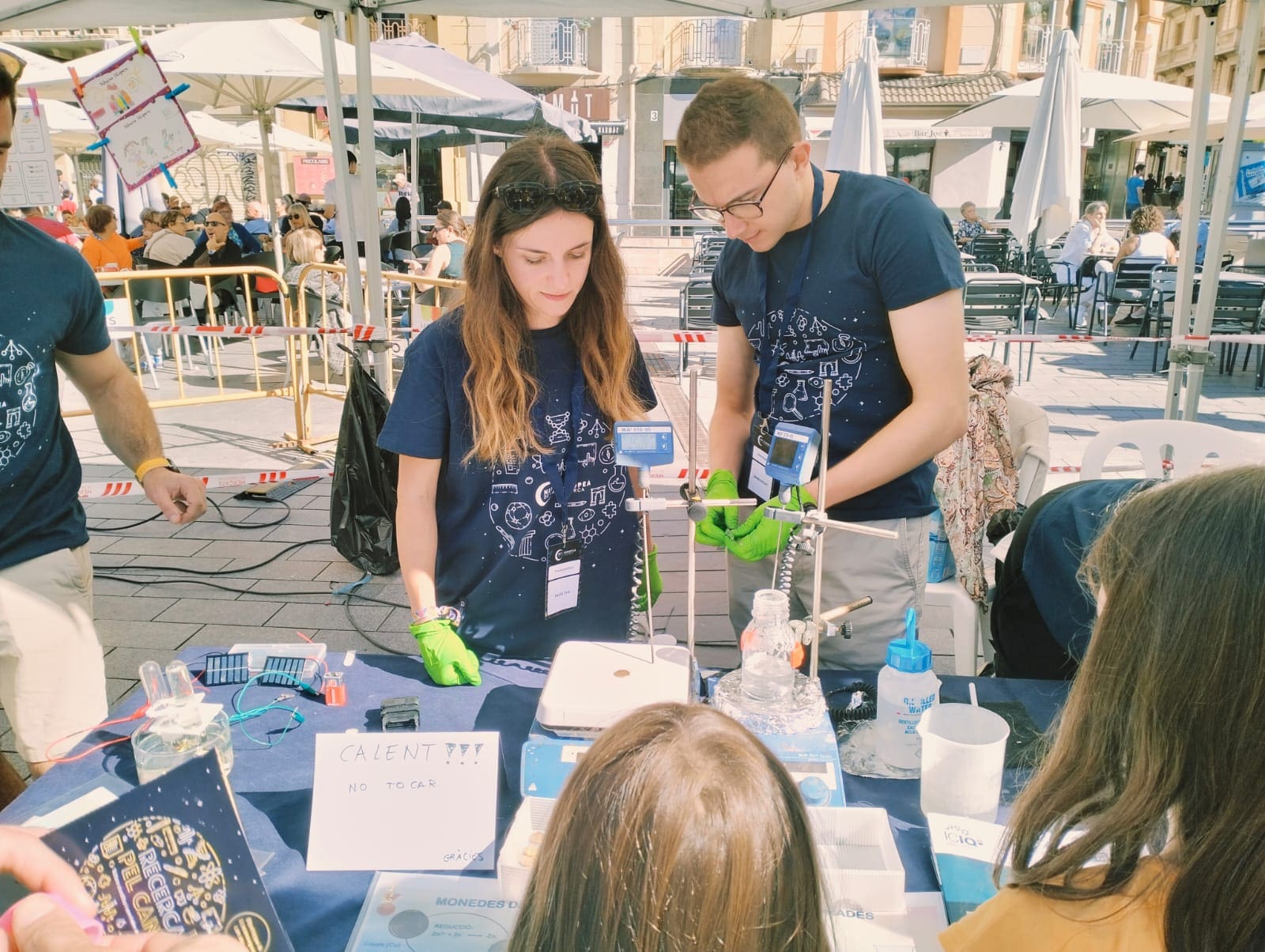

Face to face with David Cahen

Credit: Weizmann Inst. PR dept

Professor David Cahen is Professor at Bar Ilan University’s Dept. fo Chemistry and at the Department of Materials and Interfaces at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel. Cahen’s research focuses on exploring chemical means to control the electronic and optical properties of materials. He studied Chemistry and Physics at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and then moved on to Northwestern University to pursue a PhD in Chemistry and Materials Research. He conducted his postdoctoral research in biophysics of photosynthesis at the Hebrew University and at the Weizmann Institute, where he started his work on solar cells. His research has helped define the chemical limits of semiconductor miniaturisation and contributed both to the basic understanding and the practical use of several types of solar cells. His current research is aimed at understanding how complex biomolecules, such as proteins, can function as opto-electronic materials, how they can work in devices such as solar cells and sensors, as well as how to understand and improve more conventional solar cells, in terms of materials and use of light.

When did you decide to become a scientist and why?

I am curious, so I had many and diverse aspirations as a kid: from ambassador to the Pope. As I was growing up, luxuries were few and we used to get yellow cheese as a treat a few times a week. I would take this piece of cheese on my plate, and I would cut it again, again and again in order to get to the atom of cheese. I think I was seven or eight years old, I was just curious about how things work, I wanted to understand.

What do you like and enjoy the most about your job?

Being creative. For a short period, I was a synthetic chemist. I was working in creating materials that no one had ever created. It was a great satisfaction to know you are the first one to make something new. I think the act of creativity is the thing I like the most. The moment you lose that, I don’t see why you should continue doing scientific research.

Which are your greatest achievements in your career so far?

Scientifically, I have been able to contribute to the development and application of two types of (now commercial) solar cells by doing basic research. I also studied materials that were thought to be boring, from an electronic point of view, and showed that they are very interesting. But there’s one other thing: my dentist.

There’s a program that started some 45 years ago at the Weizmann Institute, where grade schools send promising but underperforming kids to get tutored at the Institute. I had three students. For two of them, I failed as a tutor, but I consider the third one a success: he is now my dentist. I helped save him from a terrible education system that was just going to leave him behind. There’re hidden treasures in people and it’s a matter of chance that we develop our best qualities.

Could you give a piece of advice to young researchers who want to become excellent researchers in their fields?

Get students who are smarter than you, because they pull you up. Peter Medawar, 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, wrote this little book called “Advice to a young scientist”. One of the central points of the book is choice of your research topic, you should focus on problems that matter. Choose a problem that if you manage to solve, it will matter to you and hopefully somebody else. That’s very wise advice, because, especially today, even if you have done something that will be considered brilliant in 20 years from now, the system is not sufficiently patient to wait that long.

You do a lot of science communication, why?

Science is a universal language, you can use it to bridge gaps. It’s a good way to start a dialogue because hopefully, scientists can’t argue too much about facts in science. After WWII, scientific collaboration is what started the relations between Germany and Israel; that’s the perfect example of how science helped bridge the gap between the two countries and make them go forward.

From your point of view, what are the most important areas in which science funding should be spent?

In 2008 Google announced it was going to become the first sustainable company in the world. They organised a conference around the topic and invited several speakers, me among them. So, Google started working on this and in 2011 they ended the program because they realised it was impossible to achieve. But, to their credit, they did a post-mortem study. Looking back, Google reached a conclusion: we don’t have the science that will enable the technology to make complete sustainability possible. Therefore, they encouraged every country and company to put aside 5 or 10% of the R&D budget for blue sky research. It’s extremely important to fund blue sky research because, in the end, it’s the crazy ideas that will give us the next stage in technology.

We see many women studying chemistry at University including at PhD level; however, we do not see that many women working as researchers or academics. Why do you think that happens and what do you propose to change the situation?

There’s no question there are more social pressures for women than for men, and I have no idea how to fight those, as it is not enough that all the possibilities are open for women like for men. It’s not simple, but I believe role models can make a difference. There are still few women at the professor level at the Weizmann Institute, but our only Nobel prize awardee is a woman: Ada Yonath! She is working closely with schools, she invites them to the institute and exposes kids to science from a very young age.

What do you do in your spare time (if you have any)?

I don’t do much, but I like to read history books and to walk in the fields, it helps me to think a little bit or put my brain in neutral mode. I also enjoy traveling – I have recently fulfilled my life dream of going to the Galapagos!

If I went to Rehovot, what should I visit?

I’m afraid there’s only the Weizmann Institute, so you’ll have to go to Tel-Aviv. The art, including music and literary scenes there are awesome – it’s one of the most creative cities I know!

Proust Questionnaire

A chemical element: Pb (read the chapter in Primo Levi’s “The Elements” on it)

Favourite Scientist: Le Chatelier as his principle explains so many seemingly surprising phenomena (if limited to those I worked with/ met: William Little, whose original thinking, even when wrong, was hard to beat.)

Your favourite invention: bicycle

If you had not been a chemist… I am a hybrid physicist/materials scientist/chemist, but I might have gone into geology if only to be more outdoors, but more seriously because it itself combines so many of the sciences.

Favourite destination: Himalaya (trekked there, twice)

A book: Guns, Germs and Steel by Jared Diamond

A film: Casablanca

A dream: Make artificial photosynthesis a useful reality

Science is… the best occupational therapy I know of

Related news

Let's create a brighter future

Join our team to work with renowned researchers, tackle groundbreaking

projects and contribute to meaningful scientific advancements

02-12-2024

02-12-2024